Jumping into Elasticsearch

It’s a quiet Saturday, it’s wet out, and I don’t feel like doing much, so I open up Netflix. We all know how that typically goes, but today I actually know what I want to watch—Mad Max: Fury Road. Part of me already knows it’s not available to stream, but I start typing it into the search bar anyway—m. Immediately suggestions starting with the letter ‘m’ fill the page (including actors’ names), which become slightly more focused with each new letter. I know I would never watch many of them, but others, eh, maybe, and others still are already favorites. And it’s all thanks to the data from my personal viewing history being put to work behind the scenes to influence the results.

Enter Elasticsearch

One piece of the monster puzzle used by Netflix to provide these types of suggestions so rapidly is Elasticsearch. Also used by a range of other companies like Facebook, Salesforce, and GitHub, Elasticsearch is a highly scalable open-source search server that runs on Apache Lucene. It works by indexing data spread across any number of nodes within a cluster, making everything searchable in near real-time (with only about one-second latency for indexing).

In this article, we’ll look into the general architecture and capabilities of Elasticsearch by loading up a local instance with mock data, and firing off some useful queries. The examples will touch on basic API usage, and I encourage you to spend extra time building on each one.

Architecture Overview

A cluster, as mentioned above, is a collection of nodes (servers). Nodes store any number of indexes, which can generally be thought of as databases of similar records, or in this case, types. A type is similar to a table within a relational database, consisting of a name and a mapping (schema) to describe a document class.

You can read more about these topics, as well as shards and replicas, in the Getting Started guide.

Set up

To simplify getting up and running, I’m going to assume you have Docker installed. (And if not… why?) With your daemon running, just throw this into the command line:

docker run -d -p 9200:9200 -p 5601:5601 psvet/elasticsearch-kibana-sense

This will result in an Elasticsearch cluster running on port 9200, which you can verify with curl <your docker host ip>:9200. We also have Kibana available for viewing our data, as well as the Sense plugin for easily interacting with the REST API, running on 5601.

In Action

Now let’s see a little of what it can do.

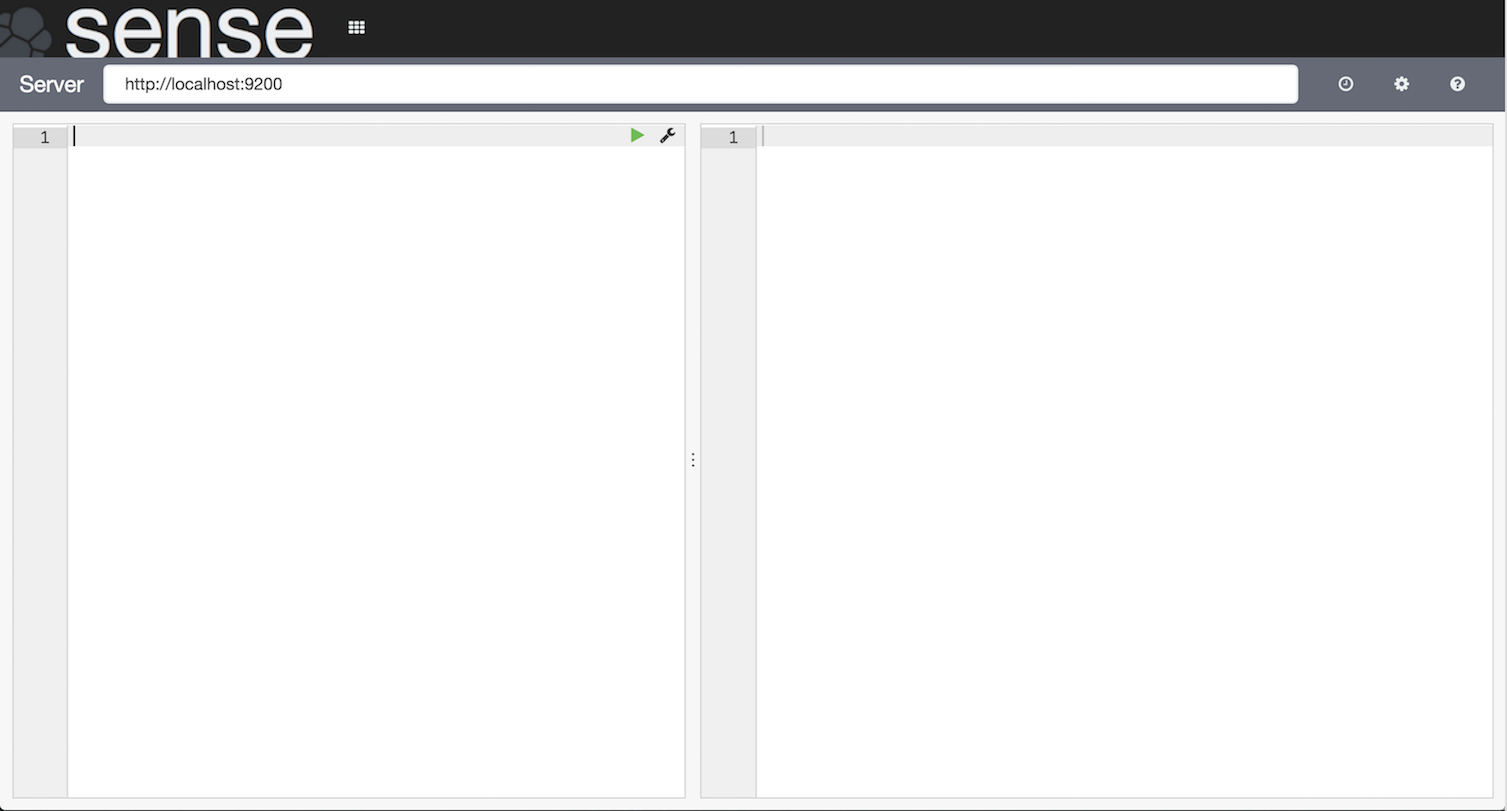

In your browser, navigate to <your docker host ip>:5601/app/sense, and you’ll see something like this:

The Elasticsearch REST API makes it possible to perform basic (and far-from-basic) CRUD operations at the index and document level (with some exceptions), as well as monitor your clusters and nodes.

Creating an index

First, let’s create an index for a bare-bones social network. In the lefthand Sense panel paste (or type, and take advantage of the awesome IntelliSense):

PUT /socialnetwork

{

"mappings": {

"user": {

"properties": {

"first_name": {

"type": "string"

},

"last_name": {

"type": "string"

},

"city": {

"type": "string"

},

"state": {

"type": "string"

},

"gender": {

"type": "string"

},

"age": {

"type": "integer"

},

"skills": {

"type": "string"

}

}

}

}

}

As you might as have guessed from the above JSON blob, in addition to creating the socialnetwork index, we explicitly mapped a user type. But I’ll let you in on a secret: we could have left out the request object (PUT /socialnetwork), then simply created a user document and let Elasticsearch handle the mapping dynamically. We could have even started creating documents without initially creating the index! All we’d have to do is change the path to /socialnetwork/user, and provide the user data in the body straightaway.

While dynamic mapping is advantageous in many ways (especially as a means of getting started with Elasticsearch, as you’ll see), you’ll find it’s not ideal for fields where a specific format might be required (dates), or if you want to restrict the type of data that can be added. With explicit mapping, we could add the

dynamicflag to the rootuserobject, as well as any individualobjectfields, and set it tofalseto quietly ignore unknown fields, orstrictto throw an exception.

Important: One major CRUD exception, as mentioned above, is that mappings cannot be updated. In such cases where that’s desired or necessary, you’ll have to create a new index and reload any existing data.

So with that said, let’s ditch this thing by running DELETE /socialnetwork, and start from scratch.

Bulk API

Now we’ll take advantage of the bulk API to create two new indexes and upload a ton of documents all at once.

First, we need to download some mock data in raw JSON format. (preview)

Then in the command line, navigate to where the data is stored, and upload it to Elasticsearch:

curl -XPOST <your docker host ip>:9200/_bulk --data-binary "@mock-data.json"

(You’ll see a huge blob of JSON full of the newly created documents.)

We left out the index and type before /_bulk in the above URI, because the file included documents for separate indexes, which were distinguished like this:

{"index":{"_index":"socialnetwork","_type":"user","_id":"1"}}

... user document data (on one line because of the `--data-binary` option)...

{"index":{"_index":"localsearch","_type":"business","_id":"1"}}

... business document data ...

You can generally narrow the scope of your requests by including the index and/or type in the URI.

Each document also has a simple integer id, but if no id is specified on creation, a unique alphanumeric string will be generated automatically.

You can perform basic CRUD on any document by specifying its id in the URI. Go ahead and run GET /socialnetwork/user/1 and you should see this response:

{

"_index": "socialnetwork",

"_type": "user",

"_id": "1",

"_version": 1,

"found": true,

"_source": {

"first_name": "Cheryl",

"last_name": "Ferguson",

"gender": "Female",

"city": "Miami",

"state": "Florida",

"age": 36,

"has_pets": false,

"skills": [

"Mining",

"OS X",

"Revenue Cycle Management",

"HSDPA",

"Commercial Piloting"

]

}

}

You see some details about the document and its location, and the data itself inside _source. As you can guess, new documents default to _version: 1, and any updates would increment the version. If we wanted to update this document, we could either make a request to PUT /socialnetwork/user/1 with any updates included in the full document object (_source, above), or more simply, we could do a partial update using /_update, like so:

POST /socialnetwork/user/1/_update

{

"doc": {

"skills": [

"Mining",

"OS X",

"Revenue Cycle Management",

"HSDPA",

"Commercial Piloting",

"Elasticsearch"

]

}

}

Notice the method is now POST, but besides that, all _update requires is mapping any updated fields inside a doc object. Run that, and you’ll see the document version is incremented:

{

"_index": "socialnetwork",

"_type": "user",

"_id": "1",

"_version": 2,

"_shards": {

"total": 1,

"successful": 1,

"failed": 0

}

}

Searching

Obviously this is what Elasticsearch is all about, but hopefully you’ll forgive the long introduction in the name of actually having data to search. Thanks to the bulk upload, our node now has a socialnetwork index with 1000 unique user documents, and a localsearch index with 500 business documents, so let’s dig in.

While Elasticsearch’s URI search capabilities are wildly robust, we’ll focus mainly on the Query DSL, and frankly still barely brush the surface.

Full-text queries

To start, let’s run a simple full-text query with match:

GET /socialnetwork/user/_search

{

"query": {

"match": {

"state": "South Carolina"

}

}

}

Fairly straightforward on the surface. The match query searches the specified field for the specified value, but the value is actually indexed and lowercased, so it looks for the words 'south' and 'carolina' (with an implicit boolean AND condition), instead of the phrase 'South Carolina'. Switching the value to 'Carolina south' returns the same result. In addition to configuring match more explicitly, you can also use the match_phrase query to search for exact phrases.

Let’s take a quick look at the response:

{

"took": 10,

"timed_out": false,

"_shards": {

"total": 5,

"successful": 5,

"failed": 0

},

"hits": {

"total": 39,

"max_score": 4.1971407,

"hits": [ ... matching documents ... ]

}

}

Along with some other metadata, we get a hits object. Inside that you’ll see the total number of matched documents, and a nested hits array containing the documents themselves. The max_score property relates to a score given to each retrieved document, which is calculated based on its relevancy. You’ll see this same type of response format for practically all searches.

Both match and match_phrase allow only one field to be searched. To match on multiple fields you can use… multi_match, like so:

GET /socialnetwork/user/_search

{

"query": {

"multi_match": {

"query": "New",

"fields": [ "city", "state" ]

}

}

}

This searches for the word 'New' in the city and state fields, and retrieves the document if there is a match in either one. You’ll notice, however, that we’re querying both fields for the same value. You can’t query fields independently with multi_match, but you’ll see a number of ways around this when we get to compound queries.

Finally, there’s match_all, which retrieves all records within the given scope, and is as simple as this:

GET /socialnetwork/user/_search

{

"query": { "match_all": {} }

}

Term-level queries

Term-level queries are good for searching for non-string values, such as numbers or dates, that aren’t analyzed and indexed as part of the full text. You can read more about searching for strings in term-level queries in the link, but in general using a full-text query is preferred.

The term query looks for documents with an exact match for the given value:

GET /socialnetwork/user/_search

{

"query": {

"term": { "age": 40 }

}

}

You can also search for numbers or dates within a certain range:

GET /socialnetwork/user/_search

{

"query": {

"range" : {

"age" : {

"gte" : 26,

"lte" : 35

}

}

}

}

As with all examples here, there are many other term-level queries available, not to mention deeper configurations for each, so please refer to the documentation for more.

Compound queries

All of the queries described so far can be combined into compound queries. This is where things really start to pick up, but we’ll continue to stay pretty basic.

The bool query uses one or more boolean clauses—must, must_not, should, and filter—each with one or more nested queries (including potentially more bool queries, with their own clauses and queries), to determine matching results. The must and filter clauses are very similar, with the only difference being that filter ignores the query’s score. The should clause contributes to the document’s score if the nested query is satisfied, but has no effect otherwise.

GET /socialnetwork/user/_search

{

"query": {

"bool": {

"should": [

{

"range" : {

"age" : {

"gte" : 26,

"lte" : 35

}

}

},

{ "term": { "has_pets": true } }

],

"must": { "match": { "state": "New York" } },

"must_not": {

"range": {

"age": { "gt": 40 }

}

}

}

}

}

Remember at the start of this Searching section I mentioned there was a localsearch index available? Let’s dust that off.

The indices query allows for searches across multiple indexes, similar to what Netflix does when including actors along with titles in their search suggestions. Here’s a simplistic example expanding upon the previous search:

GET /_search

{

"query": {

"indices": {

"indices": [ "socialnetwork", "localsearch" ],

"query": {

"bool": {

"should": [

{

"multi_match": {

"fields": [ "skills", "tags" ],

"query": "Algorithms"

}

},

{

"range": {

"age": {

"gte": 26,

"lte": 35

}

}

}

],

"must": { "match_phrase": { "state": "New York" } },

"must_not": [

{

"range": {

"age": { "gt": 40 }

}

},

{ "match": { "skills": "Art Exhibitions" } }

]

}

}

}

}

}

Here we’re looking for users that are ideally skilled in Algorithms and somewhere between 26 and 35 years old (should), definitely located in New York state (must), and definitely not older than 40 or skilled in Art Exhibitions (must_not). (Gotta draw the line somewhere. Thanks, mock data.) At the same time, we’re looking for businesses that are also in New York, and ideally have 'Algorithms' in their tags.

One thing to keep in mind when mapping type properties: if you’re going to run

indicesqueries, there is no way to differentiate between identical field names across indexes or types. For example, not that it’s an issue for us now, but we wouldn’t be able to query against a user’scityorstateindependently from a business’. Whoops. It’s not pretty, but we could distinguish them asuser_state,business_state, etc.

Pagination

You may have noticed in the previous searches that only 10 documents were ever visible, despite most having a much larger hits total. That’s because Elasticsearch defaults the size of the result set to 10, which can be increased or decreased using the size parameter, like so:

GET /socialnetwork/user/_search

{

"query": {

"match": { "city": "New York" }

},

"size": 5

}

Note that this does not affect the number of matched documents, only the visible result set. You can progress through the remaining hits from the above search with from:

GET /socialnetwork/user/_search

{

"query": {

"match": { "city": "New York" }

},

"size": 5,

"from": 5

}

Results are zero-indexed, so this puts us at the next document after the previous search. Following this would be 10, 15, and so on.

Scroll

For cases when it’s necessary to retrieve or ingest a large number of documents, the scroll API can be used to avoid the relative inefficiency involved in normal pagination. It works by keeping a “snapshot” of the search context for a specified time period, ignoring any updates to the index within that.

GET /socialnetwork/user/_search?scroll=1m

{

"query": { "match_all": {} },

"size": 50

}

In the response object you’ll find a Base-64 encoded _scroll_id, which will be used to keep the search context alive. Any remaining scroll searches will look like this:

GET /_search/scroll

{

"scroll": "1m",

"scroll_id": "<_scroll_id from previous request>"

}

Each request resets the scroll duration, so it’s only important to allow enough time for each batch to be processed—not the final total. Notice that we dropped the index and type from the URI, which are both included in the stored search context.

Important: each response includes a new

_scroll_idto use in the proceeding request. They should not be reused.

Summary

Seriously, did this even make a dent in what’s possible with Elasticsearch? It’s already a mile long and still feels insubstantial. Go explore the reference guide and you’ll find dozens of topics I didn’t even mention, but hopefully you found this to be a good starting point for going deeper. Now you should know how to create indexes and populate them with mapped types and documents (simultaneously!), as well as how to run a number of basic full-text and compound queries against them.

As a next step, be sure to try hooking up one of the available clients to a project.

Now I need to actually find something to watch.